Authors:

|

Dr Rod Dilnutt University of Melbourne |

A/Prof Sherah Kurnia University of Melbourne |

Dr Svyatoslav Kotusev HSE University, Moscow

|

Introduction

We commonly accept that Enterprise Architecture is informed by business strategy. This assumption is deeply embedded in our mainstream methodologies, so why do so many architectural projects go wrong at great operational and financial cost?

Our research has found that there are four fundamental preconditions that must be assessed before commencing any architectural development:

- Is there a well-articulated and agreed Business Strategy?

- Does this Business Strategy provide clear direction?

- Is the Business Strategy robust and have the flexibility to respond to rapid change?

- Business strategy creates legacy ICT

All of these factors were first identified in the early 1990’s however, many organisations have not heeded risk warnings (Spewak, & Hill 1992, Brown 2010; Cantara et al.; 2016: Kotusev et. al., 2016). If the return on investment from EA is to be maximised, now is the time to adopt some simple principles before proceeding to develop any architectures that risk being built on false assumptions.

The role of the business strategy for enterprise architecture

The term “business strategy” has numerous slightly different meanings and interpretations in the literature. However, it can be generally understood as “a combination of the ends (goals) for which the firm is striving and the means (policies) by which it is seeking to get there” (Mintzberg et al. 2016)

Traditionally, the notion of business strategy plays a significant role in the EA discourse and the business strategy is widely considered as a starting point, or basis, for developing EA artifacts defining the future structure of information systems required by the organization. In fact, all mainstream EA methodologies propose to start the development process of EA artifacts in some or the other form directly from the organizational business strategy, e.g. mission, vision, drivers, goals, objectives and key performance indicators (Longepe 2003; Bernard 2004, Theuerkorn 2004; .Niemann 2006; van’t Wout et al. 2010; TOGAF 2018).

For example, Holcman (2013) recommends starting the EA effort from explicitly documenting the business goals and their hierarchy list the business vision, mission, strategy, drivers and objectives as first EA artifacts of the contextual layer, which “sets the stake in the ground for the rest of the architecture by providing context”. Similarly, TOGAF (2018) lists the business strategy, goals and drivers among the primary inputs of the preliminary phase of its architecture development method (ADM). Bittler and Kreizman (2005) claim that “future-state EA is directly derived from business strategy” and argue that “the goal [of the EA effort] is to translate business strategy into a set of prescriptive guidance to be used by the organization (business and IT) in projects that implement change (Bittler & Kreizman 2005). IBM’s EA consulting method states that EA is “driven by strategy” (IBM 2006). Likewise, Oracle’s EA framework declares that “driven by business strategy” is the first of its core values (Covington & Jahangir, 2009). Essentially, all these methodologies consider the business strategy as the core input for EA initiatives.

Analogous ideas regarding the primacy of the business strategy are also expressed by other authors, who argue that EA and IT planning efforts in organizations should stem directly from the business strategy. Bernard (2003) states that “the idea of Enterprise Architecture is that of integrating strategy, business, and technology”. Parker and Brooks (2008) argue that the business strategy and EA are interrelated so closely that they represent “the chicken or the egg” dilemma. These views are supported by Gartner (2009) whose analysts explicitly define EA as “the process of translating business vision and strategy into effective enterprise change” (Lapkin et al. 2008). Moreover, Gartner analysts argue that “the strategy analysis is the foundation of the EA effort” and propose six best practices to align EA with the business strategy (Lapkin 2009). Unsurprisingly, similar views are also shared by academic researchers, who analyze the integration between the business strategy and EA (Aldea, Iacob, Quartel & Franken 2013) modeling of the business strategy in the EA context.

To summarize, in the existing EA literature the business strategy is widely considered as the necessary basis for EA and for many authors the very concepts of business strategy and EA are inextricably coupled, i.e. EA essentially cannot exist without the business strategy. Current views on the role of the business strategy for EA prevalent in literature can arguably be best summarized in the words of Schekkerman (2006), who formulates this idea thus: “No strategy, no enterprise architecture”. van’t Wout et al.(2010) echo the same view almost verbatim: “No strategy, no architecture. No vision, no architecture”.

The Issues

For organisations considering their EA there are inherent risks to be overcome. Our study has identified four key issues which if assessed prior to the EA journey may have a significant impact on successful deployment.

Is there a well-articulated and agreed Business Strategy?

Common sense tells us that there must be a Business Strategy before commencing EA development. However, Gartner (2016) reported that “two-thirds of business leaders are unclear about what their business strategy is, and what underlying assumptions it is based on”.

If the Business Strategy does not exist or has not been clearly articulated, agreed and widely communicated then there is little surprise that any EA deployed will struggle to be fit-for-purpose.

Lesson: The architect must clarify the business direction so that the EA is built on solid foundations.

Does this Business Strategy provide clear direction?

The problem of formulating business strategies and plans in a way that does not provide any clear actionable direction for EA has been recognized for a long time (Lederer & Mendelow, 1987: Segars & Grover, 1996). EA includes platforms, application portfolios, operating processes, people structures and infrastructures. However, there can be a tendency to pronounce strategy in abstract terms. This can be very difficult to interpret for subsequent EA design and deployment. For example, “general statements about the importance of “leveraging synergies” or “getting close to the customer” are difficult translate into concrete capability (Ross, Weill & Robertson, 2006).

Lesson: As EA intends to bridge the communication gap between business and IT stakeholders, facilitate information systems planning and thereby improve business and IT alignment the architect must ensure the fundamentals are clearly articulated.

Is the Business Strategy robust and have the flexibility to respond to rapid change?

Even when organizations have clear and actionable business strategy, this strategy is often unstable, frequently changing and unable to provide a steady basis for planning IT (Cantara, et al., 2016: Kotusev et. al., 2016). We live and work in a world of rapid change. This turbulence can originate from many sources including advances in technology, changed social values, regulatory obligations and marketplace expectations (Sauer & Willcocks, 2002). Internally, changes in strategy, leadership, and operating models increase the challenges to create robust yet responsive EA.

Lesson: The architect must risk assess this volatility and plan accordingly. This will always be a challenge but ‘forewarned is forearmed’ and the current focus on agility is helpful here, and activity must be planned to avoid anarchic islands of capability.

Business strategy creates legacy ICT

Finally, there is a paradox in that after being developed and deployed, ICT typically exists in organisations much longer than the business strategies or strategic initiatives they were intended to support (Wierda 2015: Ross, 2005). Even when organisations have a rather clear, actionable and stable business strategy, this strategy often requires highly specific, ICT components to create competitive advantage. However, these may have a limited shelf-life as technology and management innovations overtake their usefulness. Thus, creating the perennial problem of legacy ICT or ‘alignment traps’.

Lesson: Take a long-term view but be prepared to compromise to create business opportunity.

The role of the Architect

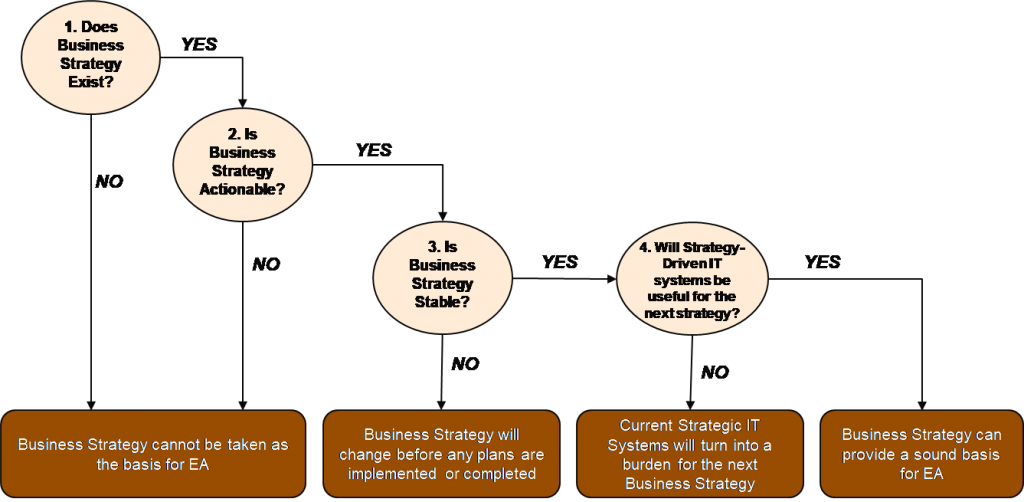

Each of these four areas require the architect to engage closely with business leadership. Only through close engagement will alignment of business strategy and EA be achieved. In some architect functions this will require a rethink of the role and development of engagement strategies and skills. A starting point can be to use the following risk assessment framework as a communication tool to provoke discussion and better understanding.

Figure 1 – Business Strategy – EA Risk Assessment

Figure 1 – Business Strategy – EA Risk Assessment

Conclusion

Our study finds that contrary to the claims on the critical importance of the business strategy for EA found in the available prescriptive and conceptual literature, this empirically substantiated analysis questions its actual significance and value as an input for EA initiatives. This inconsistency between the assumed and actual roles of the business strategy for EA initiatives can be regarded as one of the most critical questions in EA research (Kotusev 2017). However, the existing EA literature does not provide any clear suggestions regarding what other information might be necessary or desirable to support EA initiatives.

This study has important implications for both EA research and practice. From the research perspective, our findings suggest that EA scholars cannot conceptualize EA as a derivative from the business strategy and cannot reasonably assume that the business strategy provides a critical input for EA initiatives. The realities of EA seem to be more complex than it is widely believed.

From the practical perspective, our findings suggest that EA practitioners should seek some other additional information regarding the organization and its business that would be more helpful for the EA effort than the business strategy. In other words, architects should find alternative discussion points with their business colleagues to be able to plan corporate information systems in a meaningful way.

One of the study limitations is that the references supporting the four problems discussed in this paper are dispersed across a very broad body of EA and other related literature. Consequently, other potential problems with the business strategy might have been missed or unnoticed by the authors. Furthermore, this study is purely conceptual and does not leverage any first-hand empirical data to investigate the four identified problems in greater detail. Nevertheless, our study raises an important issue which is likely to provoke further research and advance our understanding of EA. Due to the evident theoretical and practical importance of these gaps, addressing the questions proposed in this paper can be considered as a worthwhile direction for future research in the EA discipline.

Close

The assumption that business strategy is the basis for EA needs to be risk assessed and evaluation of these four factors can provide the architect a sound place to start and open the dialogue with business leaders. Identification of the four problems associated with business strategy informs that assuming business strategy will provide the clarity and direction required to anchor EA as a value-adding business asset creates a significant risk exposure. However, this can be overcome by a simple risk assessment.

References

Aldea, A., Iacob, M.-E., and Quartel, D., “From Business Strategy to Enterprise Architecture and Back”, Proceedings of the 13th Trends in Enterprise Architecture Research Workshop, 2018, pp. 145-152.

Bernard, S.A., An Introduction to Enterprise Architecture, AuthorHouse, 1st edn, Bloomington, IN, 2004.

Bittler, R.S., and Kreizman, G., “Gartner Enterprise Architecture Process: Evolution 2005”, G00130849, Gartner, Stamford, CT, 2005, pp. 1-12.

Brown, I., “Strategic Information Systems Planning: Comparing Espoused Beliefs with Practice”, Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Information Systems, 2010, pp. 1-12.

Cantara, M., Burton, B., and Scheibenreif, D., “Eight Best Practices for Creating High-Impact Business Capability Models”, G00314568, Gartner, Stamford, CT, 2016, pp. 1-13.

Iacob, M.-E., Quartel, D., and Jonkers, H., “Capturing Business Strategy and Value in Enterprise Architecture to Support Portfolio Valuation”, Proceedings of the 16th IEEE International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference, 2012, pp. 11-20.

IBM, “An Introduction to IBM’s Enterprise Architecture Consulting Method”, IBM Global Services, Armonk, NY, 2006, pp. 1-17

Kitsios, F., and Kamariotou, M., “Business Strategy Modelling Based on Enterprise Architecture: A State of the Art Review”, Business Process Management Journal, Online(Online), 2018, pp. 1-19.

Kotusev, S., Singh, M., and Storey, I., “Enterprise Architecture Practice in Retail: Problems and Solutions”, Journal of Enterprise Architecture, 12(3), 2016, pp. 28-39.

Kotusev, S., “Critical Questions in Enterprise Architecture Research”, International Journal of Enterprise Information Systems, 13(2), 2017, pp. 50-62.

Lapkin, A., “Six Best Practices for Aligning Enterprise Architecture with the Business Strategy”, G00164923, Gartner, Stamford, CT, 2009, pp. 1-6.

Lapkin, A., Allega, P., Burke, B., Burton, B., Bittler, R.S., Handler, R.A., James, G.A., Robertson, B., Newman, D., Weiss, D., Buchanan, R., and Gall, N., “Gartner Clarifies the Definition of the Term ‘Enterprise Architecture'”, G00156559, Gartner, Stamford, CT, 2008, pp. 1-5.

Lederer, A.L., and Mendelow, A.L., “Information Resource Planning: Overcoming Difficulties in Identifying Top Management’s Objectives “, MIS quarterly, 11(3), 1987, pp. 389-399.

Longepe, C., The Enterprise Architecture Project: The Urbanisation Paradigm, Kogan Page Science, London 2003.

Nieman, K. D., From Enterprise Architecture to IT Governance: Elements of Effective IT Management, Vieweg, Wiesbaden, 2006.

Ross, J.W., “Forget Strategy: Focus IT on Your Operating Model”, Center for Information Systems Research (CISR), MIT Sloan School of Management, Cambridge, MA, 2005.

Ross, J.W., Weill, P., and Robertson, D.C., Enterprise Architecture as Strategy: Creating a Foundation for Business Execution, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA, 2006.

Sauer, C., and Willcocks, L.P., “The Evolution of the Organizational Architect”, MIT Sloan Management Review, 43(3), 2002, pp. 41-49.

Schekkerman, J., “Extended Enterprise Architecture Framework Essentials Guide, Version 1.5”, Institute for Enterprise Architecture Developments (IFEAD), Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2006,

Segars, A.H., and Grover, V., “Designing Company-Wide Information Systems: Risk Factors and Coping Strategies”, Long Range Planning, 29(3), 1996, pp. 381-392.

Spewak, S.H., and Hill, S.C., Enterprise Architecture Planning: Developing a Blueprint for Data, Applications and Technology, Wiley, New York, NY, 1992.

Theuerkorn, F., Lightweight Enterprise Architectures, Auerbach Publications, Boca Raton, FL, 2004.

TOGAF, “TOGAF Version 9.2”, C182, The Open Group, Reading, UK, 2018.

van’t Wout, J., Waage, M., Hartman, H., Stahlecker, M., and Hofman, A., The Integrated Architecture Framework Explained: Why, What, How, Springer, Berlin, 2010.

Wierda, G., Chess and the Art of Enterprise Architecture, R&A, Amsterdam, 2015.

Click here for a copy of the formal publication: Can Enterprise Architecture Be Based on the Business Strategy published in the proceedings of the 53rd Hawai’i International Conference on Systems Sciences 2020.